#WomensWednesday nº5 – 10th December 2025: Christine de Hemptinne (1895–1984) — Catholic Action, Gender, the Global Cold War, and the Paradoxes of Decolonization

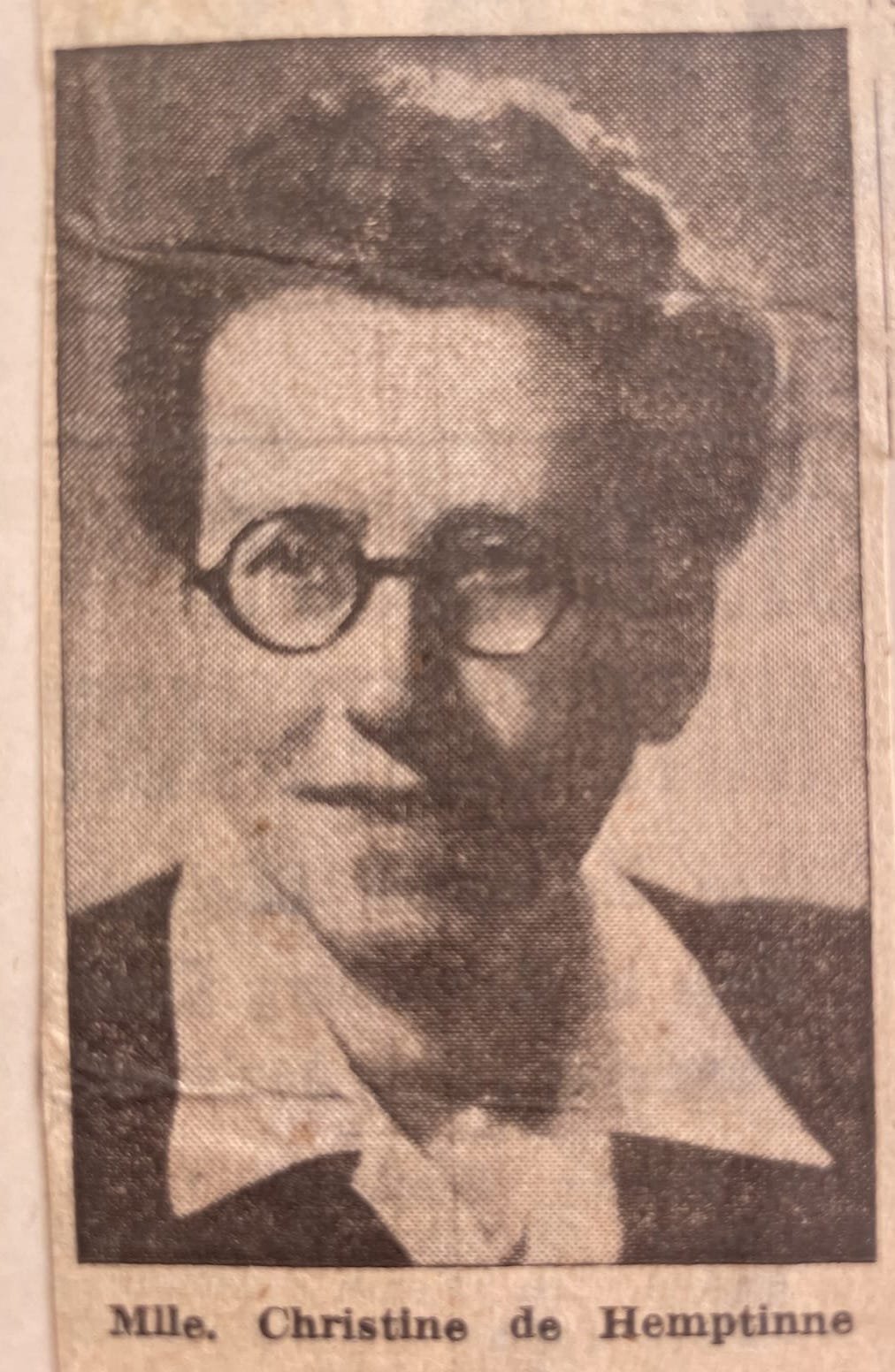

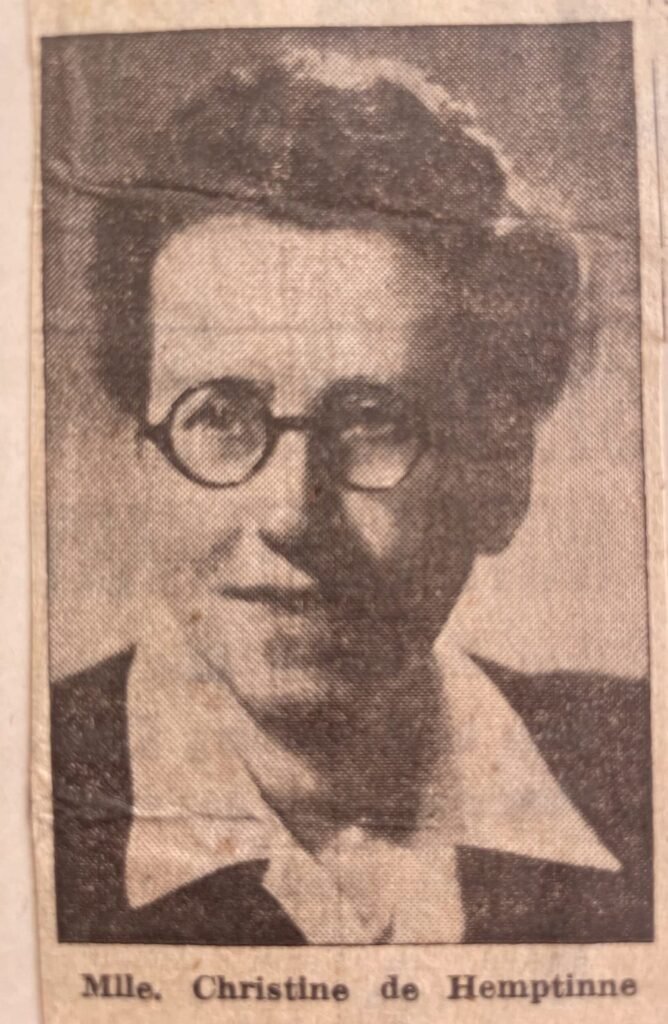

Christine Eugénie Marie Ghislaine de Hemptinne was born on 1 December 1895 in Ghent, Belgium, into an aristocrat Catholic family. Her life and work exemplify the dynamic role of laywomen in shaping Catholic internationalism during the 20th century. Combining local social engagement with global ecclesial diplomacy, she became a key figure for understanding women’s agency within Church structures and international organizations.

Early life and education

Christine received a solid education, including studies at the École de Maintenon in Paris. During World War I, she assisted her mother in caring for wounded soldiers and organized aid for prisoners of war through her father’s charitable network. These formative experiences instilled in her a lifelong commitment to social service and Catholic values.

Catholic Action and youth leadership

In the interwar period, Christine emerged as a leader in Catholic Action, the lay apostolate promoted by Pope Pius XI. In 1923, Cardinal Mercier appointed her president of the Association Catholique de la Jeunesse Belge Féminine (ACJBF), later also leading its Dutch-speaking branch, the Vrouwelijk Jeugdverbond voor Katholieke Actie (VJVKA). Her rise to leadership coincided with a pivotal moment in Catholic mobilization, as laywomen were officially encouraged to engage in apostolic efforts and social reform. This period also saw mounting tensions with women belonging to the Jeunesse Ouvrière Chrétienne (JOC), whose specialized, worker-based apostolate, rooted in Joseph Cardijn’s ‘See–Judge–Act’ method, championed greater lay autonomy and grassroots organization, a method which often conflicted with centralized and more hierarchical structures of traditional Catholic Action groups.

International Nnetworks and WFCYW

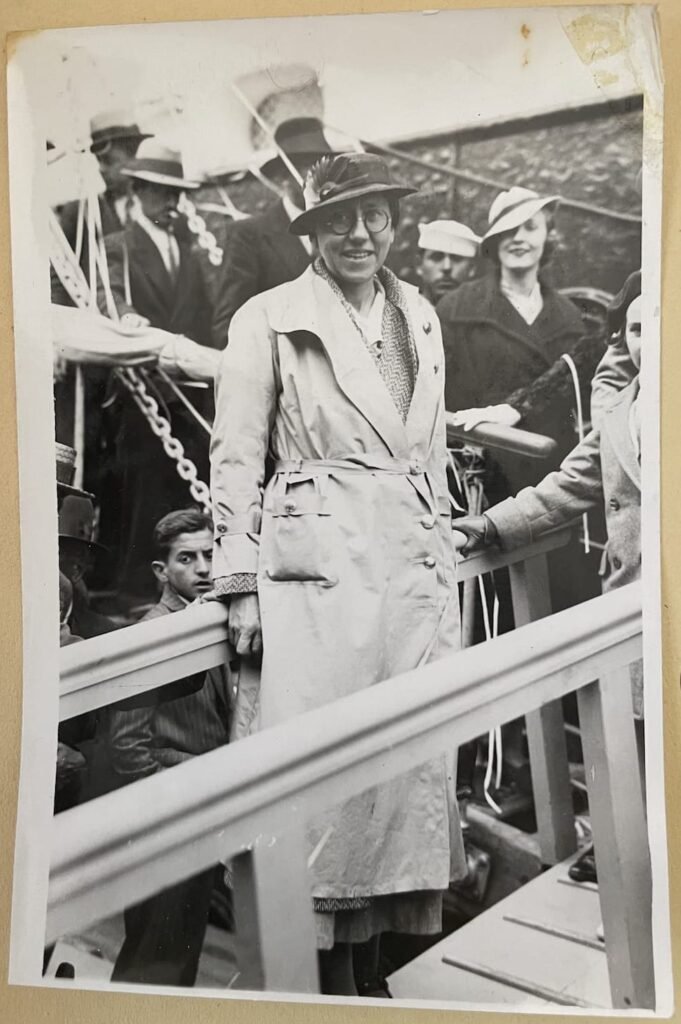

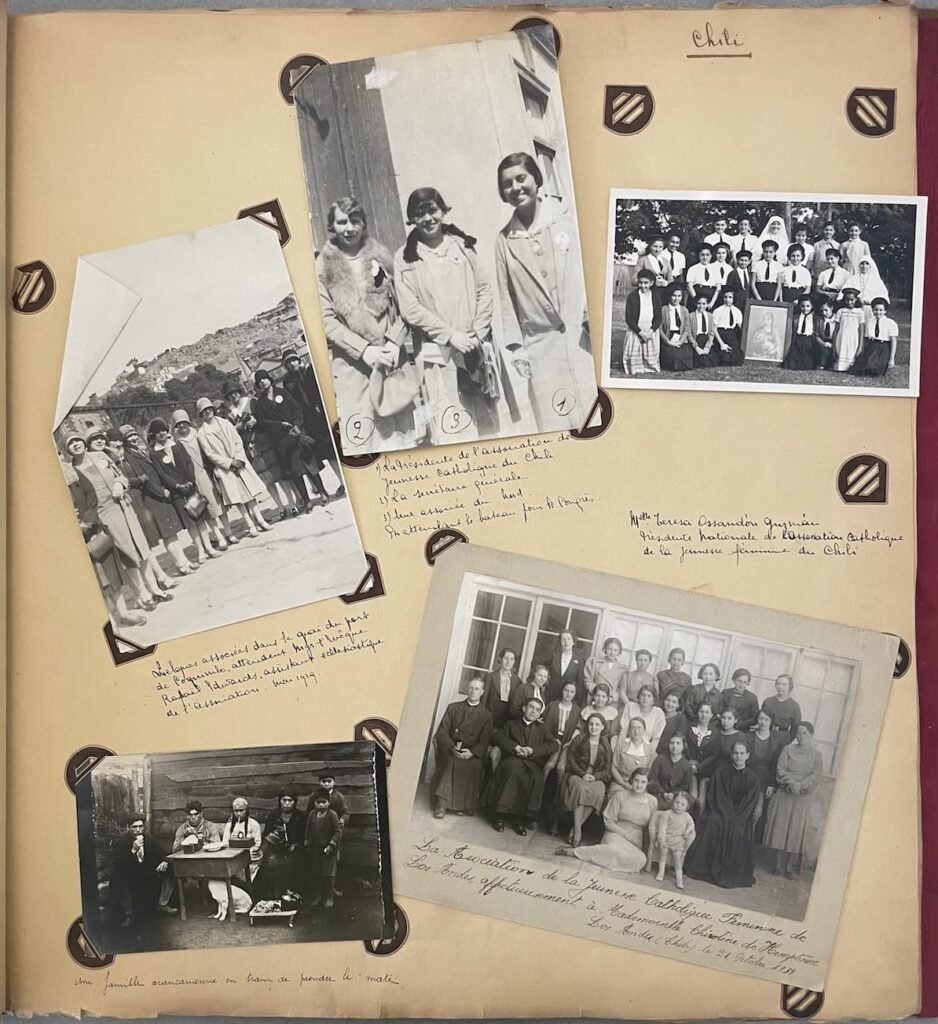

Christine’s vision extended beyond Belgium. In 1926, she co-founded the World Federation of Catholic Young Women (WFCYW) and served as its first president. This organization became one of the cornerstones of Catholic young women’s internationalism. Her linguistic skills and extensive contacts within the Catholic world —including nuncios, pontiffs, and other influential figures—enabled her to expand WFCYW’s reach. By the early 1930s, Monsignor Giuseppe Pizzardo, the Cardinal protector of the organisation, commissioned Christine to travel to South America to provide technical training to female branches in Peru, Brazil, Venezuela, Bolivia, and Chile. Acting as a personal envoy for the Roman model of Catholic Action, her journeys were widely reported by Catholic and national press, embedding gendered perspectives within Vatican diplomacy. This enabled the organisation to expand both in size and geographic reach at an exponential rate. She remained president of WFCYW until 1956 and continued as honorary president, mentoring new generations of Catholic women leaders.

Education and social work

Christine championed education as a tool for empowerment. She directed vocational schools, organized playground services for children, and in 1943 founded the Catholic Educational Centre for Social Work in Ghent, training women for professional roles in social care. These initiatives reflected her belief in combining faith with practical service, contributing to the modernisation of a gendered version of Catholic social teaching. Projects were often exported abroad but, as evidenced by the rich archive preserved at Kadoc*, they also absorbed influences from overseas—primarily from North and South America.

(*Interfaculty Documentation and Research Centre on Religion, Culture and Society at KU Leuven)

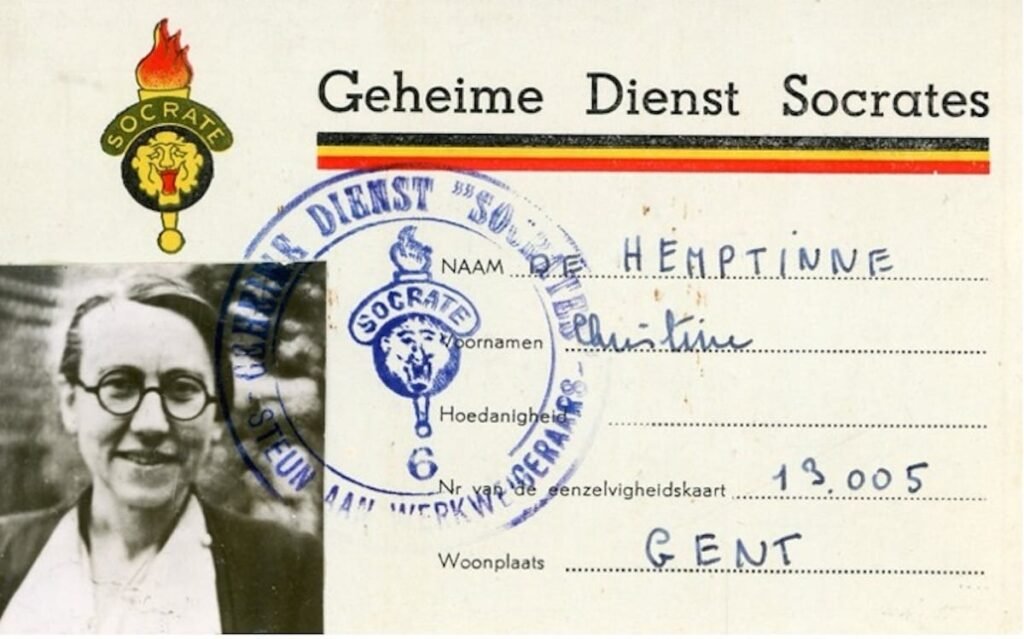

Wartime resistance and postwar reconstruction

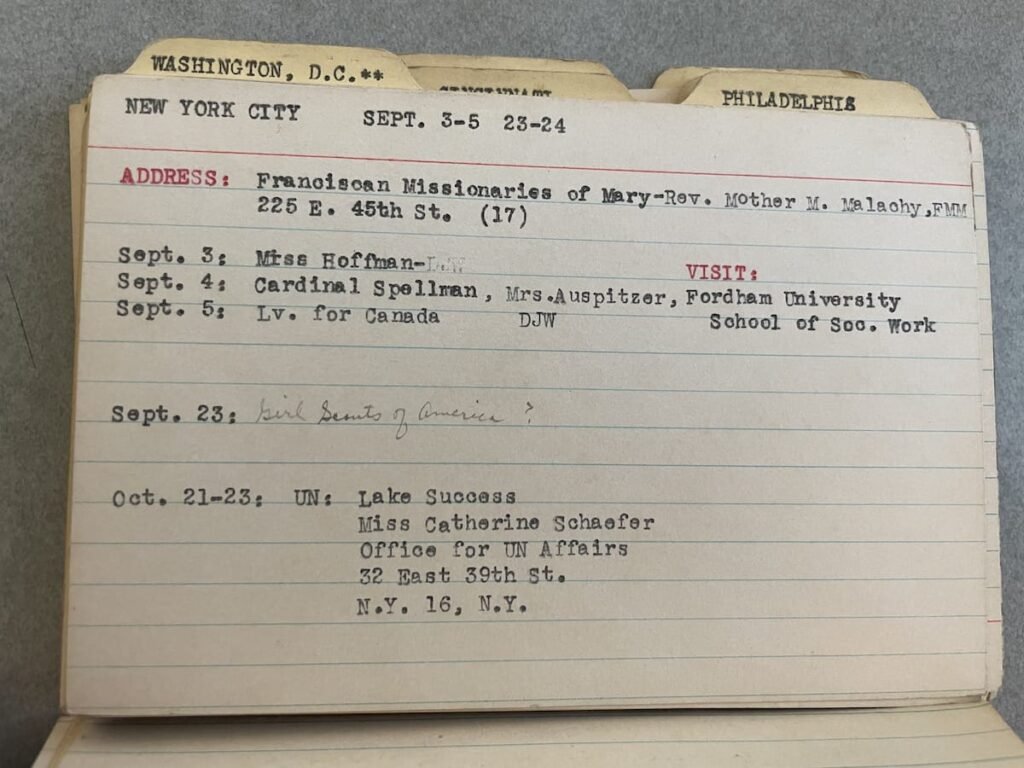

During World War II, Christine was part of the Belgian Resistance. She collaborated with the Socrates network, which specialized in intelligence and the protection of persecuted individuals, including Jews and political dissidents. Her clandestine activities earned her widespread admiration after the war. In the late 1940s, she undertook a tour of the United States and Canada, where Catholic organizations and civic groups honoured her as a war heroine, praising her bravery and moral leadership during one of history’s darkest periods.

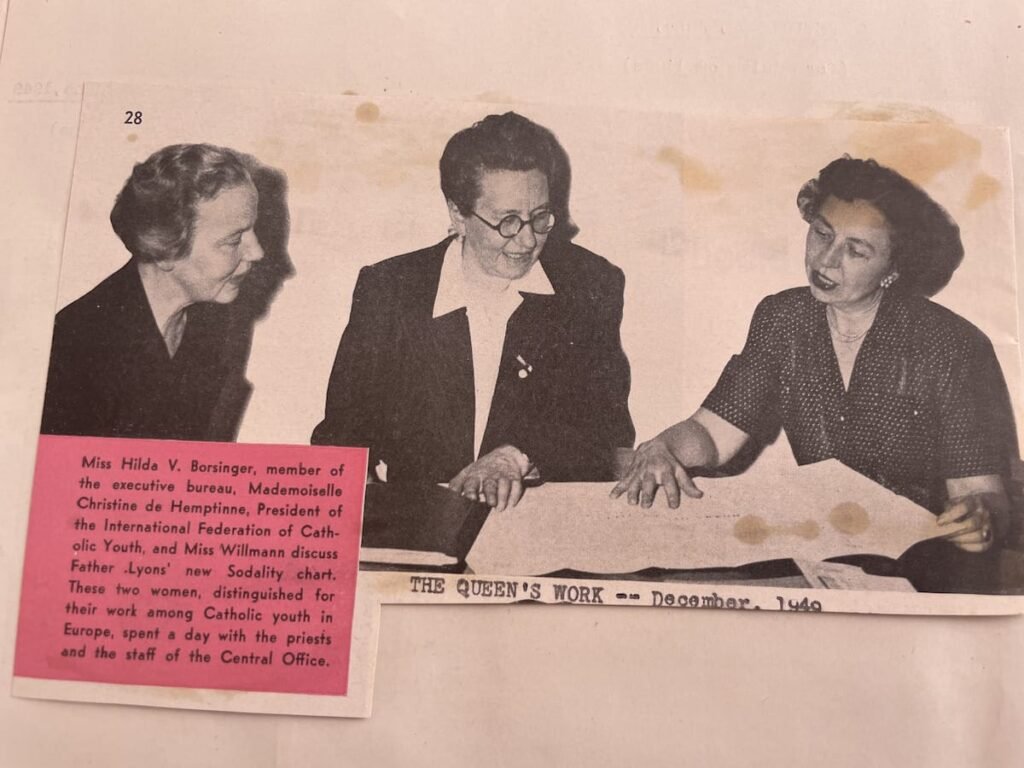

From war heroine to cold war agent

Christine’s transformation (from Catholic Action sponsor to Resistance fighter to Catholic international leader) had profound implications during the Cultural Cold War. Her international acclaim was strategically leveraged by Catholic networks to project an image of moral authority and democratic commitment in the sphere of youth. Fiercely anti-communist, her 1949 North American tour functioned as a form of cultural and religious diplomacy, reinforcing Catholic women’s legitimacy in advancing social work, achieving a degree of professionalization, and pursuing civic goals such as voting rights, while simultaneously countering secular and communist narratives and upholding a conservative stance on family, women’s bodies, and the domestic sphere. Her activism encompassed numerous conferences, interviews, press coverage, and visits to religious and political leaders. She was also part of the few Catholic laywomen to represent the World Union of Catholic Women’s Organisations in international organisations, such as the UN, Unesco, Ecosoc. Her reports were not only shared with the UMOFC and the WFCYW, but with other International Catholic Organisations and the Holy See. Despite the strong emphasis on preserving the domestic sphere and women’s call to motherhood, paradoxically, her example as a professional unmarried woman inspired laywomen to see themselves not only as guardians of faith and the family, but also as partners in shaping a global moral order amid bilateral tensions and the global decolonization process.

Complex agenda of her global work

From the mid-1950s onward, de Hemptinne expanded her international engagement, by co-organizing or actively participating in leadership and formation workshops across Africa and Asia. Her involvement in these activities highlighted her complex and ambivalent engagement with colonial territories. In these endeavours she navigated the competing imperatives of Vatican calls for “indigenisation,” Catholic social and United Nations definitions of development and women’s rights, and entrenched colonial interests.

At a time when international pressure for decolonization in may African countries was mounting, she played a prominent role in coordinating Belgium’s Catholic pavilion at Expo 58 in Brussels, an ambitious showcase of missionary efforts and development projects in Belgian Congo and Rwanda-Urundi. Presented under the motto of collaboration between Church, state, and the people for the concord and well-being of the African population, the pavilion featured the flags of more than 150 religious institutes and employed modern media (films, photomontages, and sound installations) to project an integrated, utopian and still rather patronising vision of Catholic-led civilisation, welfare, and hygiene. The Belgian Congo’s “village indigene” continued a long practice of dehumanizing Africans at universal exhibitions by displaying them in a ‘primitive’ state to be observed by fair visitors.

This high-profile initiative positioned Christine as a key cultural diplomat, yet it also revealed the contradictions faced by many European and U.S. (Catholic) agents of internationalism, who often struggled to reconcile their humanitarian ideals with the enduring realities of colonial power and history.

Keywords: Catholic Action, WFCYW, women’s leadership, Belgium, social work, Catholic internationals, international Catholic networks, Resistance, Socrates network, laywomen, decolonisation, mission civilisatrice.

Sources:

- ODIS database : https://www.odis.be/hercules/toonPERS.php?taalcode=nl&id=9108

- Christinne de Hemptinne fonds at the Interfaculty Documentation and Research Centre on Religion, Culture and Society (KADOC) KU Leuven*

- All photos belong to the Christinne de Hemptinne fonds at the KADOC, folders: BE.942855.194-532.1; BE.942855.2358.KFH178; BE-942855-194-910_001; BE.942855.2541.

(*Natalia Núñez Bargueño wishes to express her gratitude to Patricia Quaghebeur, Kristien Suenens and Roeland Hermans)

Further reading:

- Loffman, Reuben A. “De Hemptinne, the Benedictines and Catholic Assimilation on the Congolese Copperbelt, 1911–1960.” Journal of Ecclesiastical History 71, no. 4 (2020): 798–817. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022046920000044

- Masquelier, Juliette. Femmes catholiques et modernité: Belgique, 1918-1968. Louvain-la-Neuve: Presses universitaires de Louvain, 2019.

- Stanard, M. (2005). ‘Bilan du monde pour un monde plus déshumanisé’: The 1958 Brussels World’s Fair and Belgian Perceptions of the Congo. European History Quarterly, 35(2), 267–298.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0265691405051467