Women’s Wednesday: Launching the Digital Archive of Lay Women

To celebrate this year’s International Women’s Day, TheoFem is launching a new initiative: Women’s Wednesday, a biweekly publication forming part of the Digital Archive of Lay Women.

This space aims to bring visibility to the lives, legacies, and contributions of laywomen—those often overlooked in official narratives. It also seeks to highlight and support the work of women scholars whose research sheds light on these histories, ensuring their perspectives and contributions are recognized within academic and public debates.

By critically engaging with the histories of laywomen, this online archive seeks to challenge archival silences, interrogate traditional narratives, deconstruct stereotypes and reconstruct women’s participation in international organisations during the post-Second World War reconstruction, the Cold War, decolonization efforts. It also aims to illuminate their active role in the grassroots movement for the aggiornamento of the Church in the mid-20th century. The bulletin will feature contributions from guest researchers and specialists, as well as from Dr. Núñez Bargueño.

Why Do We Need a Digital Archive of Lay Women?

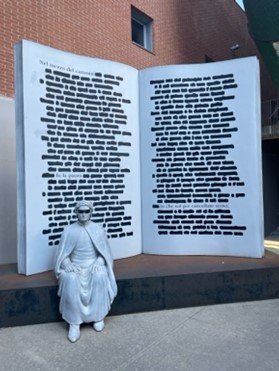

Archives are essential tools for researchers, but they are far from neutral. As Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida reminded us, archives are sites of power, and at times, they can also be places of exclusion and even violence. Decisions are made about what to preserve and what to discard. These choices shape historical memory, often privileging voices that align with dominant perspectives. As the inspiring work of Patricia Owens has demonstrated, women’s histories —particularly those of women of colour, immigrant women, and working-class women— have frequently been marginalized, if not erased entirely, from significant historiographical endeavours.

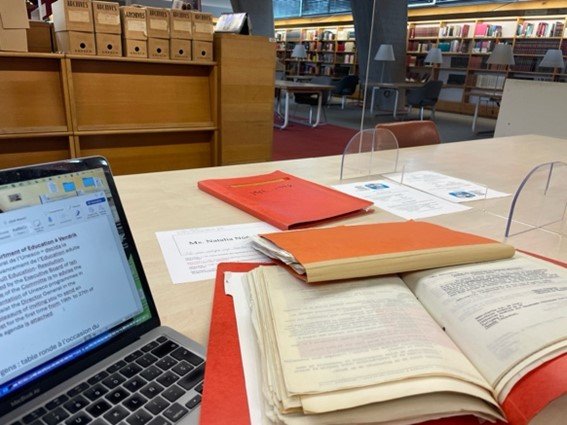

Even when records on women do exist, they are often overlooked due to non-traditional formats, implicit biases in cataloguing, or the male-centred language often used to frame historical events. This is particularly evident in institutional archives, like those at the Vatican, which hold a vast wealth of material but often are difficult to navigate when searching for the contributions of women. During my recent research stay, I found that uncovering their presence required prior knowledge of their engagement in the UN and its related agencies during the mid-20th century, as well as their frequent exchange with important members of the Curia and the hierarchy —otherwise, their impact risked remaining invisible. To help me navigate this maze I made use of my previous visits to national and local archives, such as, the Archivo Acción Católica Española – SUMMA – UPSA (Salamanca, Spain), the Centre national des archives de l’Église de France, and the Archivio dell’Azione cattolica e del movimento cattolico, ISACEM. Having preliminary notes from these archives helped me prepare to instinctively and resolutely look for these women in the Vatican archives. The process was labour-intensive and time-consuming, yet ultimately both intellectually challenging and deeply rewarding —an archival archaeology of sorts.

Reading Between the Silences

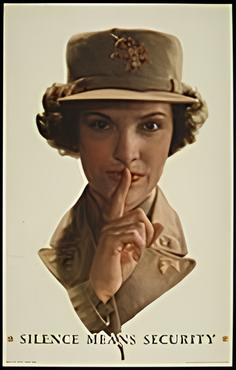

As Rodney G. S. Carter argues, archivists constantly make choices that amplify some voices while silencing others. These silences can be structural —resulting from funding constraints or restrictive access policies— but they can also be intentional. Some archives remain closed simply because the institutions that hold them wish to control the narrative. In my own research, four of the key archives I need to consult are either completely or partially inaccessible, and none are fully catalogued. Gaining access to such sources is often a challenge —it requires patience, negotiation, and, above all, trust.

Building relationships with archivists is essential. A reciprocal exchange of information not only enriches historical inquiry but also helps both researchers and archivists better understand and critically interrogate the archive itself. Demonstrating the significance of a particular perspective or project can be crucial in convincing an archivist of the importance of dedicating time, resources, or trust to making certain collections accessible. Similarly, the insights and support I have received from archivists have been truly invaluable. Throughout my work, I have sought to acknowledge the dedication and expertise of these professionals, whose labour is essential to preserving and making history accessible.

This bulletin seeks to foster dialogue and, in doing so, build the trust needed to open access to sources that, while not yet available, could prove invaluable, not only for research but also for the institution itself. Daniele Menozzi has recently underscored the significance Pope Francis places on renewing the study of Church history, viewing it as essential not only for civic society but also as a vital foundation for the formation of new priests and pastoral workers. A deeper, more inclusive and nuanced understanding of social reality is crucial for meaningful and effective pastoral engagement. As the women of the group La revuelta de las mujeres de la Iglesia (The revolt of women in the Church) remind us, it is essential to create a more inclusive Church, one that fully acknowledges those who remain at its margins, including well and bad-behaved women, people of the Global South, and LGBTQ+ communities. As this bulletin will highlight, the case of laywomen is particularly significant, not only because they represent a substantial part of the Church —at least in numbers— but also, because they have played vital roles in shaping its evolution. Their contributions have been instrumental in key areas such as the apostolate, the laity, Christian intellectuality, ecumenism and governance, particularly since the mid-1940s.

In the meantime, as historians, our task is not only to analyse what has been preserved (or made available) but also to interrogate what is missing. Naming a silence subverts it, by drawing attention to and reflecting upon what (or whom) has been omitted. Feminist, postcolonial, and critical cultural theories offer essential tools for reading against the archival grain (or silences), helping us uncover traces of those who have been un/consciously rendered in/visible. Walter Benjamin’s vision of history as a constellation of fragments reminds us that even within archival gaps, there are clues, whispers or snapshoots of lives that once were, and that are waiting to be heard and seen.

The Responsibility of Creating and Using Archives

While we work to unearth hidden or fogotten histories, we must also remain critical of our own methods. For instance, efforts to reconstruct women’s pasts should not inadvertently obscure the voices of other marginalized groups, particularly laywomen outside the English speaking world, and additionally, Europe and North America. The Vatican’s transnational archives, for instance, reflect a predominantly Eurocentric perspective of cosmopolitanism and universalism, necessitating further efforts to read against the archival grain in order to nuance and deconstruct this powerful un/conscious perspective.

Looking Ahead

Through Women’s Wednesday, I will highlight stories of laywomen who shaped Catholic transnational networks, participated in global institutions, and left an often unacknowledged mark on history. By building this Digital Archive of Lay Women, I hope to contribute to a more inclusive historical narrative: one that does justice to the complexities, struggles, and achievements of women whose contributions should no longer remain in the background.

Join the conversation, every two weeks, as we uncover and reflect upon the lives and thoughts of these remarkable women. Let’s read between the silences, together.

Cited Works:

Benjamin, Walter, 1892-1940. Illuminations, Schocken Books, 1969.

Bush, Barbara, “Searching for the ‘Invisible Woman’: Working with (and subverting) the archives”, WHN, March 24, 2013 https://womenshistorynetwork.org/searching-for-the-invisible-woman-working-with-and-subverting-the-archives/

Carter, Rodney G.S. “Of Things Said and Unsaid: Power, Archival Silences, and Power in Silence”, Archivaria 61: Special Section on Archives, Space and Power, Spring, 2006, https://archivaria.ca/index.php/archivaria/article/view/12541

Derrida, Jacques, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. Eric Prenowitz, Chicago, 1996.

Foucault, Michel, The Archaeology of Knowledge, trans. A.M. Sheridan Smith, London, 1974.

La Revuelta de las Mujeres de la Iglesia: https://www.revueltamujeresenlaiglesia-alcemlaveu.com/

Núñez Bargueño, Natalia, “Varón y Mujer Los Creó: Hacia Una Lectura ‘a Contracorriente’ de La Historia, El Género y La Religión”, Alcores: revista de historia contemporánea, nº23, 2019, pp. 17-34.

Owens, Patricia, Erased: A History of International Thought Without Men, Princeton University Press, 2025.

*All images come from Wikimedia Commons and Europeana.