#WomensWednesday nº6 & 1st Collaboration – 7th January 2026: Ellen Ammann (1870–1932): A Pioneer of Catholic Social Reform and Women’s Political Mobilization in Bavaria

Post by: Professor Yvonne Maria Werner,

LUX, Historiska institutionen, Lunds universitet

Ellen Ammann was a Swedish-born Catholic social reformer, educator, and politician whose work left a lasting imprint on Bavarian Catholic social life in the early twentieth century. Her life and achievements illustrate how religious conviction, social engagement, and women’s emerging public roles converged in early twentieth-century Europe.

Early Life and Religious Formation

Born in Stockholm in 1870 as Ellen Sundström, Ammann grew up in an educated and socially engaged family milieu shaped by liberal Protestant values, civic responsibility, and a strong commitment to education. She converted to Catholicism at a young age and, in 1890, moved to Munich following her marriage to the German orthopaedic surgeon Ottmar Ammann. This move placed her at the heart of Bavarian Catholicism at a time when ultramontane identity was a defining cultural and political force.

Ultramontane Networks and Ecclesiastical Relations

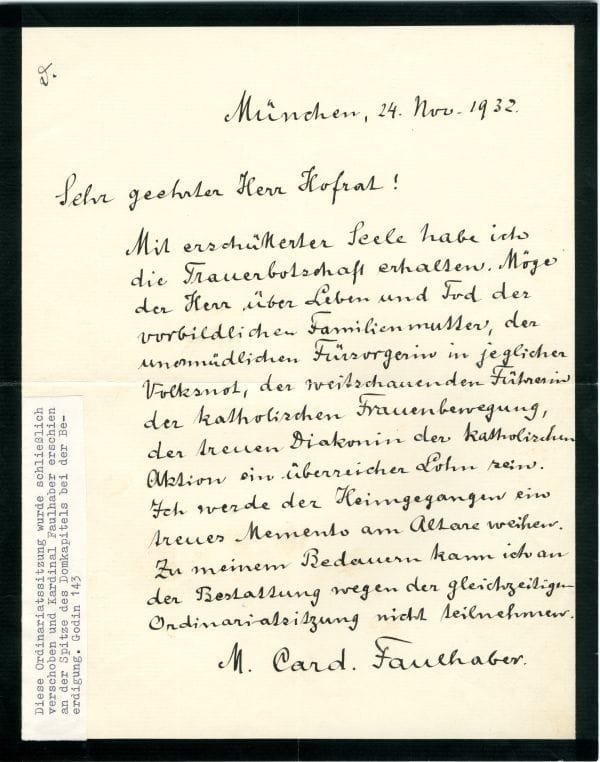

In Munich, Ammann became closely associated with leading representatives of Bavarian ultramontane Catholicism. She cooperated with the Capuchin friar Coelestin Schwaighofer, who enjoyed close ties to the Bavarian royal family, and later with the Jesuit priest Rupert Mayer, beatified in 1987. She also maintained close relations with Cardinal Michael Faulhaber, Archbishop of Munich–Freising from 1917.

Together, these figures embodied the ultramontane movement that had emerged in the nineteenth century in response to secular ideologies and to Protestant and Prussian dominance within the unified German Empire. Politically represented by the Bavarian Catholic People’s Party (Bayerische Volkspartei), ultramontanism constituted a central pillar of Bavarian Catholic identity. Ammann fully shared this confessional outlook, while at the same time translating it into modern forms of social organization and female leadership.

Institutional Innovations and Social Work

Ammann’s most enduring contribution lay in the professionalization of Catholic social work. In 1909 she founded Women’s School for Social and Charitable Work in Munich, one of the first Catholic institutions in Bavaria dedicated to training women for social service as a vocation. The school combined Catholic social teaching, practical training, and ethical formation, and drew inspiration from contemporary Protestant and international models, most notably those developed by Alice Salomon, while remaining firmly rooted in Catholic caritas.

Earlier initiatives such as the Marianischer Mädchenschutzverein (1895) and the Bahnhofsmission Munich (1897) addressed the needs of young women migrating to the city, providing protection, guidance, and social support. Through these institutions, Ammann contributed to the emergence of preventive and pedagogically informed welfare practices within Catholic contexts.

Catholic Women’s Movement and Political Engagement

In 1911 Ammann played a key role in establishing the Katholischer Frauenbund in Bayern, which became a major force within the Catholic women’s movement. She articulated a model of Catholic women’s public engagement grounded in moral authority, social responsibility, and professional competence rather than political radicalism.

Following the First World War, Ammann entered formal politics as a member of the Bavarian Parliament (Landtag) from 1919 until her death in 1932. Representing the Bavarian Catholic People’s Party, she focused on youth welfare, family policy, and social legislation. Her political stance combined confessional conservatism with a strong commitment to social reform

Ammann also became an early and decisive opponent of National Socialism. Her most dramatic political intervention occurred during the Beer Hall Putsch in 1923, when she mobilized governmental and parliamentary actors to counteract the coup attempt. Ammann’s role in halting the march of Adolf Hitler and his paramilitaries underscores her early recognition of the existential threat posed by National Socialism and her readiness to apply political authority in defence of constitutional order.

Transnational Ties and Influence on the Swedish Catholic Mission

Ellen Ammann maintained close contact with her Swedish homeland and closely followed developments within the Catholic Church there, not least through her mother Lilly, as evidenced by their extensive correspondence. She also exerted a certain degree of influence. That the Jesuits at St. Eugenia Church in Stockholm did not, as decided in 1910, withdraw from the Swedish mission was partly due to her efforts, as was the appointment in 1923 of the Bavarian prelate Johannes Müller as the new Apostolic Vicar following Bishop Bitter.

In this context, Ammann was able to draw on her strong connections to the nuncio Eugenio Pacelli, the future Pius XII. Müller, who had been a member of the cathedral chapter of the Archdiocese of Munich–Freising since 1911 and was actively involved in diocesan youth work, was personally well acquainted with Ellen Ammann. It was she who prepared him for his task as Apostolic Vicar in Sweden by teaching him the Swedish language and informing him about the conditions of the Swedish mission. Her eldest son, Albert, was a Jesuit and served as a priest in the St. Eugenia parish during the 1920s.

Legacy and Historical Significance

Ellen Ammann died in 1932, but her legacy has endured in the institutions she founded, in the professionalization of Catholic social work, and in the shaping of Catholic women’s public roles. In recent years, her legacy has attracted renewed attention. Institutions bearing her name, academic conferences, and systematic archival efforts within the Archdiocese of Munich–Freising have contributed to a renewed historical evaluation of her contributions. Discussions concerning the possible initiation of a beatification process reflect her continuing relevance within contemporary Catholic memory culture. Her life provides a compelling case study of religious modernity and the intersection of gender, faith, and social reform in the early twentieth century.

*Photos come from: Archive of the Catholic German Women’s League (Archiv des Katholischen Deutschen Frauenbundes)

Special thanks: Natalia Núñez Bargueño wants to thank profesor Werner for her kind collaboration with TheoFem. Looking forward to future collaborative endeavours!

If you are interested to be a part of this digital archive of laywomen and contribute with your research, please contact us on natalia.nunezbargueno@kuleuven.be or via the project’s social media (X and Instagram). Looking forward to hearing from you!